By Brett & Kate McKay, The Art of Manliness – July 27, 2012 at 12:56PM

Supreme Allied Commander. Head of the American Occupation Zone in Germany. Chief of Staff. President of Columbia University. Supreme Commander of NATO. President of the United States of America.

To read a list of the positions that Dwight D. Eisenhower held during his life truly makes you reflect on what a remarkable man he really was.

And yet in researching Eisenhower’s accomplishments over these past couple of months, the thing that struck me the most was how truly unremarkable most of his life was–how late in his career he emerged into history-changing prominence.

Thus of all the lessons I have gleaned from Ike’s life, this has been the most memorable: to work and train hard every day and every year, even when it seems your efforts are fruitless, because you never know when you will be called upon to lead others through a crisis, and when your goodness will get the opportunity to become greatness.

A Long Season of Stagnation: 30 Years of Missed Opportunities and Disappointments

After graduating from West Point in 1915, Eisenhower was given various assignments which largely revolved around coaching Army football teams, training officers, and organizing new units.

In 1917, as the United States began to mobilize its armed services for entry into WWI, Eisenhower had the same ambition as every other West Point graduate: to get to Europe and into the field. Ike applied several times for overseas duty, and was denied each time—rejections he found quite “distressing.”

Instead, having been noticed by superiors as a “young officer with special qualities as an instructor,” he ended up at Fort Leavenworth, training provisional lieutenants and supervising all of the regiment’s physical training, from bayonet drills to calisthenics.

Ike tried to focus on the fact that by “preparing young officers to lead troops,” he was making a “constructive contribution” to the war effort. But he found the prospect of once again being stuck training and organizing units “one of falling into dull routine” and mighty discouraging:

“For one thing, all West Point traditions that nourished élan and esprit centered on battlefield performance. The leadership of the men who had gone before us, faced with headlong attack, stubbornly defending and then causing their troops to follow them was in our minds the hallmark of a true solider. My mastery of paper work, even of rudimentary training methods, hardly seemed a shining achievement for one who had spent seven years preparing himself to lead fighting men…

Some of my class were already in France. Others were ready to depart. I seemed embedded in the monotony and unsought safety of the Zone of the Interior. I could see myself, years later, silent at class reunions while others reminisced of battle…It looked to me like anyone who was denied the opportunity to fight might as well get out of the Army at the end of the war.”

Eisenhower’s gloomy mood lifted when he was ordered to Camp Meade in Maryland to organize and equip the 301st Tank Battalion, a unit he was told would be shipping out for overseas duty. In March 1918, Ike got word that the battalion would soon be embarking from New York, and that Ike would be going along in command! Eisenhower could barely hide his exuberance from others, and went to NYC to make sure every detail was taken care of, so his men would be ready to ship out without a hitch.

Just two days later, he was back at Camp Meade. His chief told him he was impressed with Ike’s “organizational ability” and that this ability was needed to set up a new training camp in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This was another great disappointment for Ike; “my mood,” he remembered, “was black.” But he was told the assignment was temporary, and that after this training operation was completed, he’d again be considered for an overseas assignment. So Ike threw himself into whipping Camp Colt into shape, and took pride in the fact “that not a single man of ours was turned back from port because of any defect in his instructions, records, and physical condition.”

Ike’s superior, Colonel Welborn, was so pleased with Eisenhower’s masterful training of the troops, that he offered to promote him to full colonel if he agreed to give up his plans for overseas service. Ike not only declined the offer, but told Welborn he’d take a reduction in rank if it would ensure the opportunity to serve in Europe. Seeing that Ike could not be dissuaded from his desire to see combat, Welborn promised to put him in command of a November shipment of troops.

When November 1918 finally arrived, Ike had picked the men he wanted to take with him to the Western Front, had pondered strategy, and had practiced tactics with the troops. He had prepared for every detail…except one: the surrender of the Germans.

With the Armistice signed, Ike’s hope of being shipped overseas vanished; this was the war to end all wars, it was said, and thus when it came to ever getting a field command, Eisenhower was miserable he had “missed the boat:”

“As for my professional career, the prospects were none too bright. I was older than my classmates, was still bothered on occasion by a bad knee, and saw myself in the years ahead putting on weight in a meaningless chair-bound assignment, shuffling papers and filling out forms. If not depressed, I was mad, disappointed, and resented the fact that the war had passed me by.”

Eisenhower thought about leaving the Army and becoming a civilian like many of his classmates had done. But he decided to stay in. Looking on the bright side, Ike saw that his “education had not been neglected.” He had gotten the opportunity to take what he had learned in his textbooks and get real world practice in how to “take a cross-section of Americans and convert them into first-rate fighting troops and officers.” And he was grateful that his military career brought him into contact “with men of ability, honor, and a sense of high dedication to their country.”

After the war, Eisenhower trained more troops, advanced and advocated for the use of the tank (along with his friend, George Patton), became an executive officer to General Fox Conner in Panama, coached more football, attended the Command and General Staff School (graduating first out of 245 officers) and the Army War College, wrote battlefield guides as part of the Battlefield Monuments Commission, and served as a deputy to the Secretary of War, studying how to prepare for the next major conflict.

After a stint as chief military aide to General MacArthur, the Army’s Chief of Staff, Ike was itching to serve with the troops again. But when MacArthur was made Military Advisor to the Philippines in 1935, the General insisted on Ike coming along with him to act as his assistant in developing the Filipino army in preparation for that country’s independence.

In the Philippines, Ike again carried out his duties to the utmost and even learned how to fly. But as hostilities increased in Europe, he realized that the U.S. could not stay out of the war for long, and he wished to get home as soon as possible to be part of the imminent preparations for battle. MacArthur told Ike he was “making a mistake,” and that “the work [he] was doing in the Philippines was far more important than any [he] could do as a mere lieutenant colonel in the American army.”

In reply, Eisenhower reminded the general “that because the War Department had decided I was more useful as an instructor in the United States than as a fighting man in World War I, I had missed combat in that conflict. I was now determined to do everything I could to make sure I would not miss this crisis of our country.”

Eisenhower returned to the States and to active duty again, training the troops and commanding a battalion; he was ready to jump into the war effort with both feet, and was elated when he got a letter from Patton in 1940, saying that if war broke out he was sure he’d be given command in the new armored division and would make Eisenhower regimental commander under him when that happened. Ike dreamt about this prospect for weeks. Then, as it had many times before, “the roof fell in.” Ike received a telegram asking him to join the War Department Staff in D.C. as part of the War Plans Division. “Shock waves of consternation hit me,” Eisenhower remembered. The telegram sent Ike “into a tailspin;” after his many years “of constant staff assignments,” he felt he “really deserved troop duty.” But now it seemed a very real possibility that he would be left out of this war, just as he had the previous one.

While Ike wasn’t sent immediately to the War Plans Division after all, he was assigned various other staff positions, ending up as Chief of Staff for the Third Army, where his success overseeing practice maneuvers did not go unnoticed; he was given the star of brigadier general.

Then, in the wake of Pearl Harbor, General George Marshall summoned Ike to the War Department in D.C., putting him at a desk in the Planning Section and then as Chief of Operations. The possibility of ever getting field command had never seemed so remote.

Marshall, who had felt that too many staff officers had been promoted compared to field commanders during WWI, one day saw fit to blurt out to Ike: “The men who are going to get the promotions in this war are the commanders in the field, not the staff officers who clutter up all of the administrative machinery in the War Department and in higher tactical headquarters. The field commanders carry the responsibility and I’m going to see to it that they’re properly rewarded.”

He then turned directly to Ike and said: “Take your case. I know that you were recommended by one general for aviation command and by another for corps command. That’s all very well. I’m glad they have that opinion of you, but you are going to stay right here and fill your position, and that’s that!”

To which Marshall added: “While this may seem a sacrifice to you, that’s the way it must be.”

At that moment, Ike’s long-simmering resentment from not getting overseas in 1918, mixed with his umbrage at Marshall’s insinuation that he was anxious about his promotion prospects, prompting him to angrily reply: “General, I’m interested in what you say, but I want you to know that I don’t give a damn about your promotion plans as far as I’m concerned. I came into this office from the field and I am trying to do my duty. I expect to do so as long as you want me here. If that locks me to a desk for the rest of the war, so be it!”

Eisenhower almost immediately regretted his angry response, knowing it had helped neither man nor made Marshall’s job any easier. He told his son he figured the outburst had sealed the deal for him: he would forever remain a brigadier, and an assistant to other men.

And so it was a great shock to Eisenhower, when, just 3 days later, Marshall promoted him to major general and sent him to command the European Theater of Operations.

It was 1942 and Eisenhower was 52 years old. He had been in the Army for 30 years but had never held a troop command above a battalion and had no real accomplishments to his name. He had been highly praised over the course of his career, but no one knew how he’d perform outside the duties of a staff officer. But Ike had always felt confident in his ability to rise to the challenge. He had prepared himself. And now, at an age when many men begin to think of retirement, he finally had a chance to prove it.

In November 1942, he was made the Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force of the North African Theater of Operations, and oversaw Operation Torch and the Invasion of Sicily. Then in December 1943, FDR chose Eisenhower as the Supreme Allied Expeditionary Commander. And that is how after 30 years of largely unremarkable service in the Army, Dwight D. Eisenhower came to be the man responsible for pulling the trigger on Operation Overlord–the largest amphibious military assault in the history of the world. And how he gained a war hero reputation that led to two terms in the White House.

Forget Yourself and Get to Work

The ups and downs, hopes and disappointments that shaped the course of Eisenhower’s life really speak to me as a man. Eisenhower was always hoping to get the opportunity do great deeds, to do something extraordinary, to test himself and finally put all his theoretical training to work. And yet these hopes were dashed over and over again, leaving Ike to feel as though life was passing him by and would remain forever workaday.

While these disappointments would blacken his moods for a while, Ike never let his setbacks make him cynical or feel that his less exciting duties were pointless. Instead, he put the focus on his work, helping others, and making the best of whatever situation he found himself in. He kept on studying military history and strategy. He took pride in training his men to excellence, and in giving those who fell behind more chances to reach their potential. As he remembered about his pre-brigadier days:

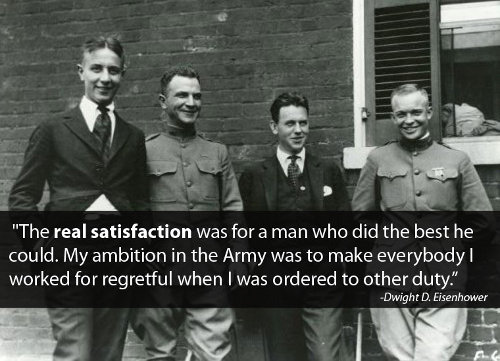

“Happy in my work and ready to face without resentment, the bleak promotional picture, I had long ago refused to bother my head about promotion. Whenever the subject came up among the three of us at home, I said the real satisfaction was for a man who did the best he could. My ambition in the Army was to make everybody I worked for regretful when I was ordered to other duty.”

While in some ways Ike’s work ethic seemed to work against him—he was so good at training and organizing that his superiors couldn’t bear to send him into the field–eventually his commitment to doing his duty over attaining personal glory was exactly what put him in position for greatness.

Reflecting on his outburst with General Marshall later in life, Ike wondered if “the years of indoctrinating myself on the inconsequential value of promotion as a measure of an Army man’s worth influenced my reply to him,” and whether if he not angrily replied as he had, “General Marshall would have had any greater interest in me than he would have in any other relatively competent staff officer.”

As an older man in retirement, Ike sought to impart the lessons he had learned to young people who were suffering the same kind of disappointments he had experienced earlier in his life:

“Since coming to Gettysburg to make our home after leaving the Presidency, I sometimes receive letters from young people, men and women in their thirties as well as high-school and college students, in which an underlying theme recurs. This theme is expressed by the question, in one form or another, “What can I do?”

What is happening, of course, is that they are, in part, in the grip of youth’s eternal conviction that most of what they are studying, and much of what they are working on, is pointless or irrelevant or futile. Added to this is the probability that in an age where atoms appear to threaten life and automation seems to threaten vocation, they feel that they may be losing their identity and any control over their destiny. Either implicitly or explicitly, the letter writers tend to blame forces beyond their control.

Those who write really want more inspiration than explanation, but at least they are questioning and that is healthy in itself. Their letters cannot be answered by one of my old proverbs or succinct statements of rosy optimism.

I could say, if we were talking together, “My friend, I know just how you feel. Everyone, including ancients like myself, feels the same as you do at times. The only thing to do is keep questioning but keep plugging.” I never make that reply. It would be fast rejected as the pat answer of a man who, already in the evening of life, does not appreciate what happens when day to day work seems sterile or purposeless.

On the other hand, it is easier to point out that if they were to examine the correspondence of any of their heroes out of history, they might find that he had revealed his feelings in pessimistic moments in the same sort of letters. I’ve done no special research but George Washington’s letter, written in the autumn of 1758, months before the fall of Fort Duquesne and the collapse of the French empire in the Ohio Valley, would be an example. As he camped at Fort Cumberland, a hundred miles or so from the enemy, he was doing absolutely nothing, in his judgment, toward victory. He put his feelings this way (capitalization, punctuation, and spelling are General Washington’s):

‘We are still Incamp’d here, very sickly; and quite displeased at the prospect before Us. That appearance of Glory once in view, that hope, that laudable Ambition of serving Our Country, and meting its applause, is now no more!’ …

Washington got his gripes off his chest, much in the mood of those who write me, by putting them down on paper. Then he went back to work.

To me, his method makes good sense. Early letters of mine displayed a dazzling ignorance of coming events. Whenever I had convinced myself that my superiors, through bureaucratic oversight and insistence on tradition, had doomed me to run-of-the-mill assignments, I found no better cure than to blow off steam in private and then settle down to the job at hand.”

Eisenhower admitted that “the cure is never total,” and added that because he could so keenly appreciate the letter writers’ gloom “when the road traveled seems to have a dead-end” it troubled him that he could not “express [himself] more eloquently and helpfully” on the subject.

Perhaps what Eisenhower was struggling to convey is that lasting success comes to those willing to spend a lifetime preparing.

A Good Man, A Great Man

Stephen Ambrose begins his 1990 biography of Ike this way:

“Dwight David Eisenhower was a great and good man. This is an assertion I hope to prove; let me begin by defining the terms.

In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower wrote his childhood friend Swede Hazlett on the subject of greatness. Ike thought greatness depended on either achieving preeminence in ‘some broad field of human thought or endeavor,’ or in assuming ‘some position of great responsibility’ and then so discharging the duties ‘as to have left a marked and favorable imprint upon the future.’

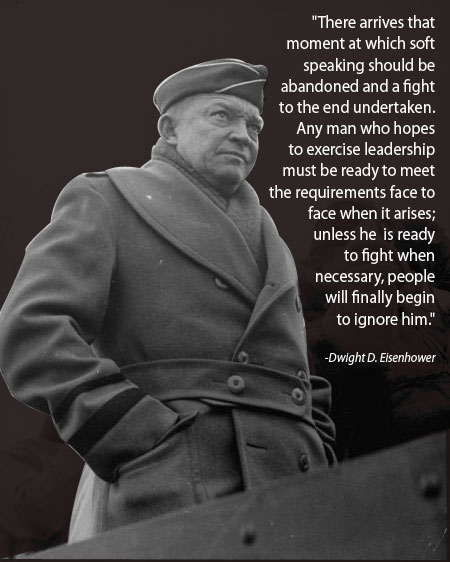

The qualities of a great man, he said, were ‘vision, integrity, courage, understanding, the power of articulation, and profundity of character.’ To that list, I’d add two others: decisiveness (the ability to take command, decide, and act) and luck.

The qualities of goodness in a man, I believe include a broad sympathy for the human condition, that is, an awareness of human weakness and shortcomings and a willingness to be forgiving of them, a sense of responsibility toward others, a genuine modesty combined with a justified self-confidence, a sense of humor, and most of all, a love of life and of people.

Eisenhower was one of the outstanding leaders of the Western world of this century. As a soldier he was professionally competent, well versed in weaponry, decisive, courageous, dedicated, popular with his men, his superiors, and his subordinates.

As President, he was a leader who made peace in Korea and kept peace thereafter, a statesman who safely guided the free world through one of the most dangerous decades of the Cold War, and a politician who captured and kept the confidence of the American people. He was the only President of the twentieth century who managed to preside over eight years of peace and prosperity.

As a man he was good-looking, considerate of and concerned about others, loyal to his friends and family, ambitious, thin-skinned and sensitive to criticism, modest (but never falsely so), almost embarrassingly unsophisticated in his musical, artistic, and literary tastes, intensely curious about people and places, often refreshingly naive, fun-loving—in short, a wonderful man to know and be around. Nearly everyone who knew him liked him immensely, many—including some of the most powerful men in the world—to the point of adulation.”

To me Eisenhower’s life serves as a potent metaphor for manhood. For much of his career he had the skills and the training to do great things, but as a member of the Nomad generation, it seemed he lived in a time that had no need of those skills…until one day they did. Even when it seemed there would never be another war, he kept himself ever ready to serve.

Today there is much talk of men being obsolete–that masculine traits are no longer necessary in the modern world. Men aren’t needed anymore…until they are.

Every man can strive to develop the qualities of a good and great man; he needn’t wait for an emergency to spur him into action. For some men, their lives will intersect with a crisis that calls upon the talents and skills they have spent years cultivating, presenting them with an opportunity to serve and lead and become a great man. No man knows if and when such a chance will arrive; in 1940 Eisenhower, looking at the fixed way he would likely ascend the Army’s ranks in peacetime, thought he’d only be able to reach colonel before he retired, and told his son he thought his chances of ever earning even a single star were practically “nil.”

Whether the chance for a man to lead in a dramatic way ever comes or not, doesn’t matter. The man who spends a lifetime cultivating the traits of goodness and greatness enjoys the confidence of being ready for whatever comes and the competence to handle the small emergencies in his day-to-day life. He will be revered for generations by family and loved ones, and if fate requires him to exercise the traits of greatness, will be remembered by history books as well. Either way, he will be able to look back at the end of his life with the satisfaction of knowing it was well-lived.

Related posts:

- Leadership Lessons from Dwight D. Eisenhower #2: How to Not Let Anger and Criticism Get the Best of You

- Leadership Lessons from Dwight D. Eisenhower #1: How to Build and Sustain Morale

- Leadership Lessons from Dwight D. Eisenhower #3: How to Make an Important Decision

- Leadership Lessons from Ernest Shackleton

- Lessons in Manliness: Chuck Yeager

Apple is now distributing v2.0.0 updates for some of the optional voices in OS X, notes AppleInsider. If not already loaded, the voices can be installed by clicking “Customize” in OS X Mountain Lion’s upgraded Dictation & Speech panel. If an update is needed, Apple is currently distributing the v2.0.0 files via Software Update. Each download is described as delivering “pronunciation and clarity improvements.”…

Apple is now distributing v2.0.0 updates for some of the optional voices in OS X, notes AppleInsider. If not already loaded, the voices can be installed by clicking “Customize” in OS X Mountain Lion’s upgraded Dictation & Speech panel. If an update is needed, Apple is currently distributing the v2.0.0 files via Software Update. Each download is described as delivering “pronunciation and clarity improvements.”…

One of the more useful and interesting features in OS X Mountain Lion is Dictation, which allows you to speak to your Mac and have your words translated to text. It’s system-wide, and works in any app where text can be entered. Before you dive in and start speaking to your Mac, here’s how to use it to its fullest.

One of the more useful and interesting features in OS X Mountain Lion is Dictation, which allows you to speak to your Mac and have your words translated to text. It’s system-wide, and works in any app where text can be entered. Before you dive in and start speaking to your Mac, here’s how to use it to its fullest.

Columbus City Health Commissioner Teresa Long and Mayor Michael Coleman might have the highest salaries in the city of Columbus, but a retired police commander collected the city’s biggest paycheck last year.

Columbus City Health Commissioner Teresa Long and Mayor Michael Coleman might have the highest salaries in the city of Columbus, but a retired police commander collected the city’s biggest paycheck last year. One of the more interesting features of OS X Mountain Lion is the ability to synchronize messages between iMessage on your iPhone and Messages on your Mac. This means you can start a conversation on your Mac and continue it on your iPhone.

One of the more interesting features of OS X Mountain Lion is the ability to synchronize messages between iMessage on your iPhone and Messages on your Mac. This means you can start a conversation on your Mac and continue it on your iPhone.  First off, you need to setup iMessages on your iPhone and change your Caller ID.

First off, you need to setup iMessages on your iPhone and change your Caller ID. With iMessages enabled it’s time to get it syncing with Messages on your computer.

With iMessages enabled it’s time to get it syncing with Messages on your computer. No system is immune to hangs and freeze-ups, and that includes even the most austere Linux desktop. What sets Linux apart is a key that can call out to the core kernel to un-freeze your desktkop, kill memory-hogging services, and cause a clean restart.

No system is immune to hangs and freeze-ups, and that includes even the most austere Linux desktop. What sets Linux apart is a key that can call out to the core kernel to un-freeze your desktkop, kill memory-hogging services, and cause a clean restart.

If you’re wondering what iCloud even is, you’re not alone. Apple launched iCloud last fall with iOS5 and we’ve

If you’re wondering what iCloud even is, you’re not alone. Apple launched iCloud last fall with iOS5 and we’ve